About The Imaginary 20th Century

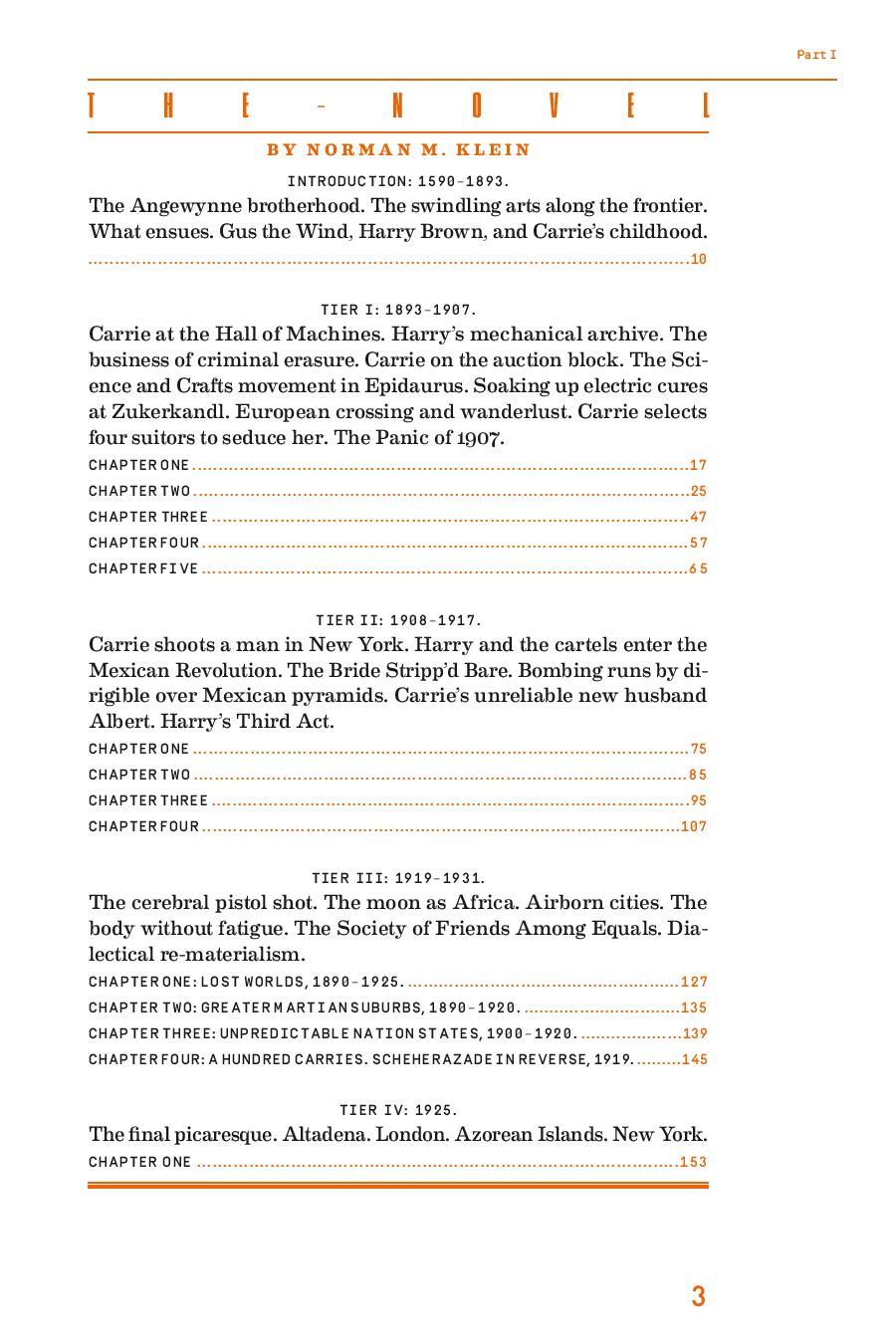

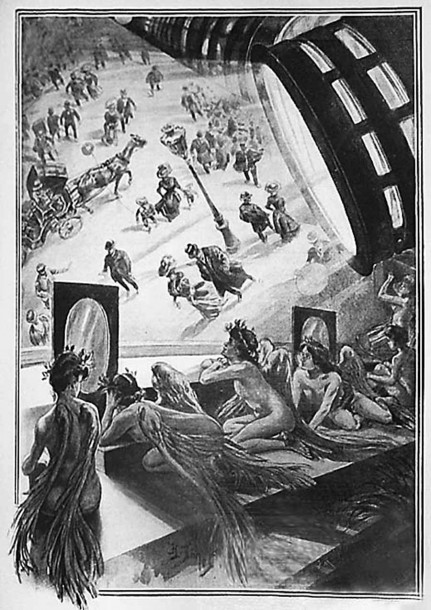

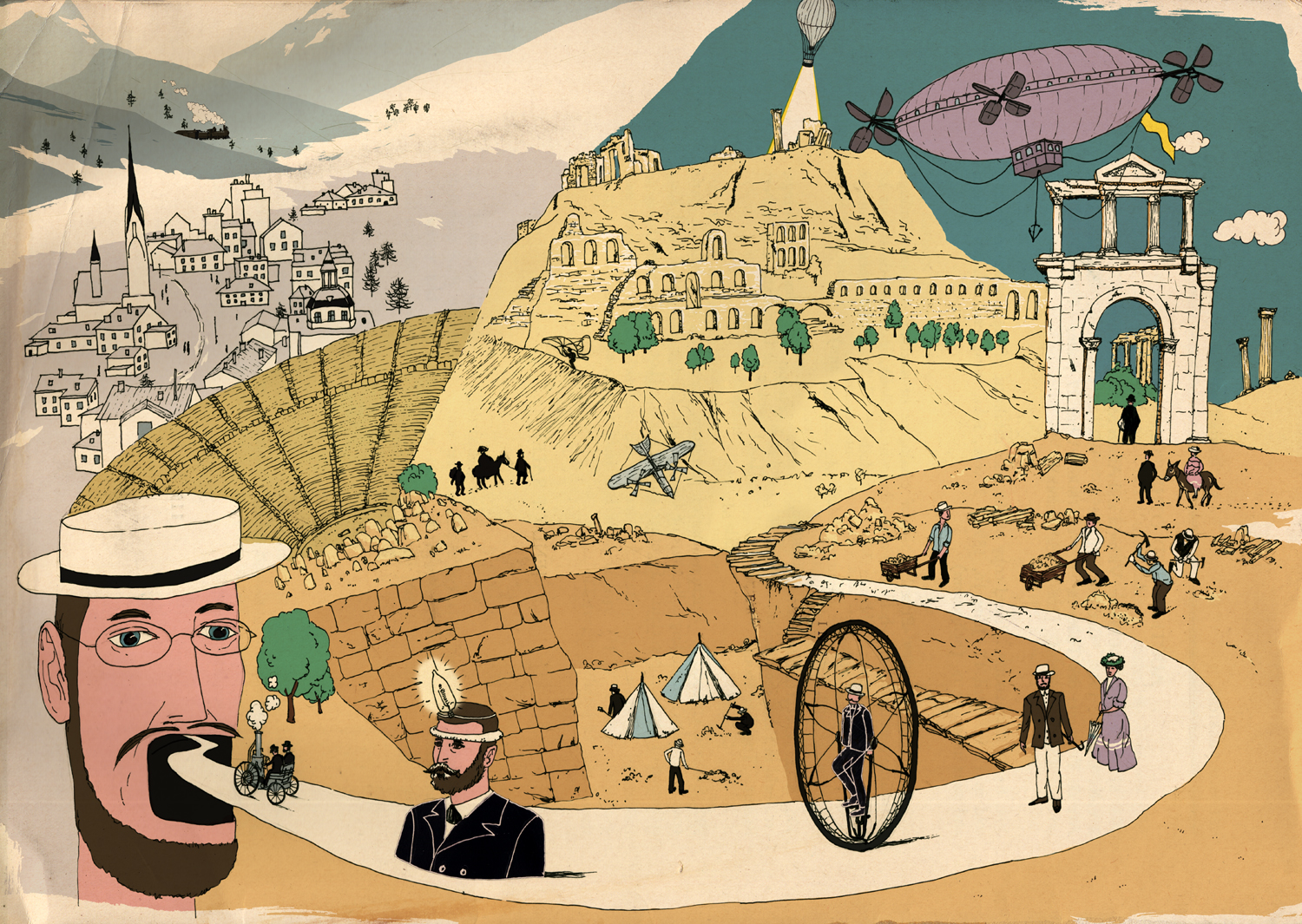

The Imaginary 20th Century is a tale of seduction as well as espionage, of archiving and the poetics of excavation.

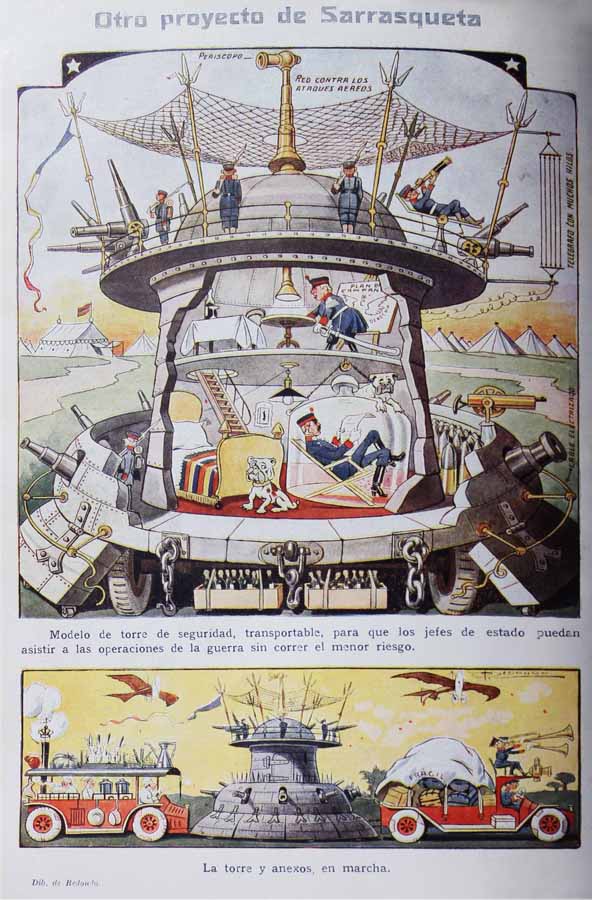

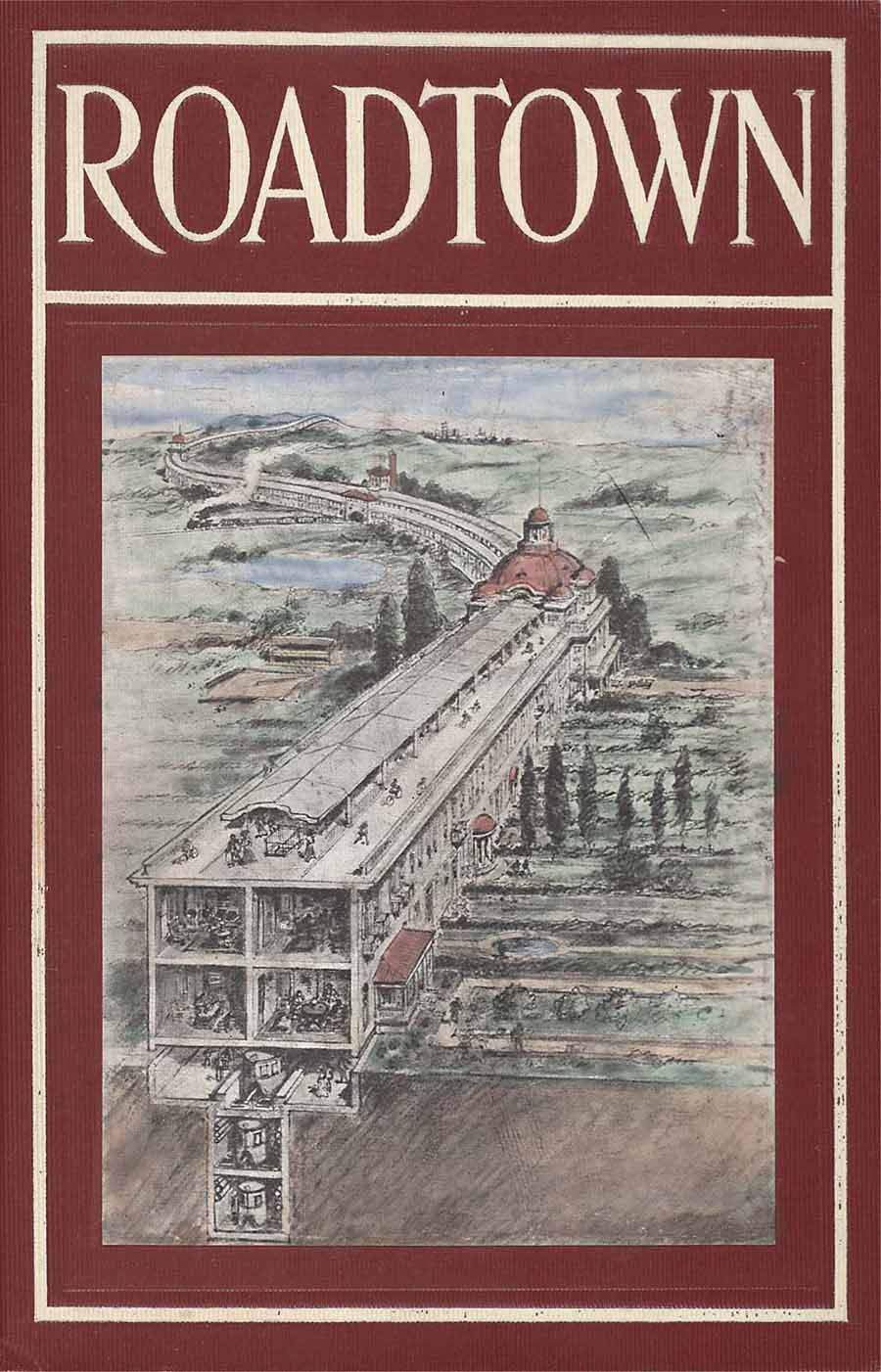

In 1901, a woman named Carrie, while traveling in Europe, invites four men to seduce her, each with a version of the coming century. At least this is how the legend comes down to us. Inevitably, the future spills off course. We navigate through the suitors’ worlds; follow Carrie on her travels; discover what she and her lovers forgot to notice. Gradually, we discover that Carrie’s misadventures with her suitors are implicated in her uncle’s world of business and espionage. For over forty years, Harry Brown was hired to erase crimes for the oligarchs of Los Angeles and the banking industry of New York. A pioneer in how to troll, hack, and manipulate the truth, Harry often used American myths of progress and future technologies in the cover-ups. As he liked to say, fiction is more believable than fact; and espionage is a form of seduction.

In 1917, Harry sets up a massive archive of his niece’s life and legend. The archive records his obsessions with Carrie and also the various world events where he intervened. In 2004, the remains of Carrie’s archive was unearthed in Los Angeles. Thereafter the federal government allowed a few scholars to study and decode it.

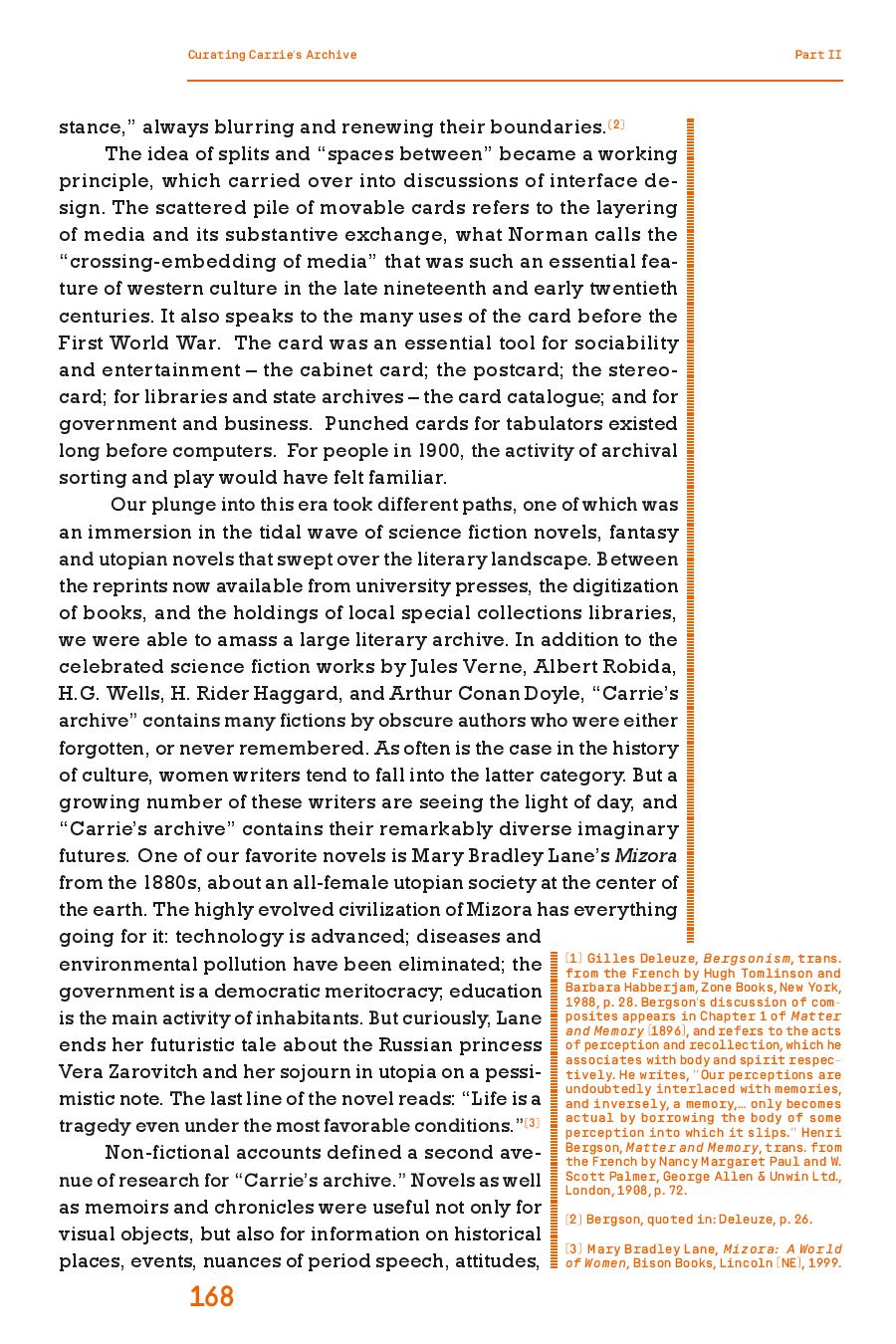

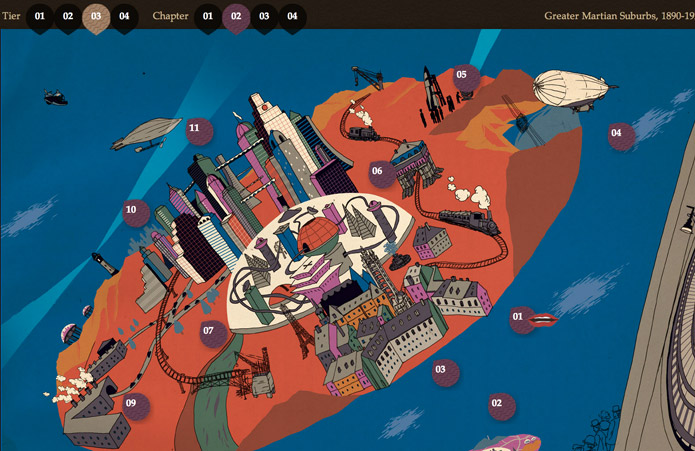

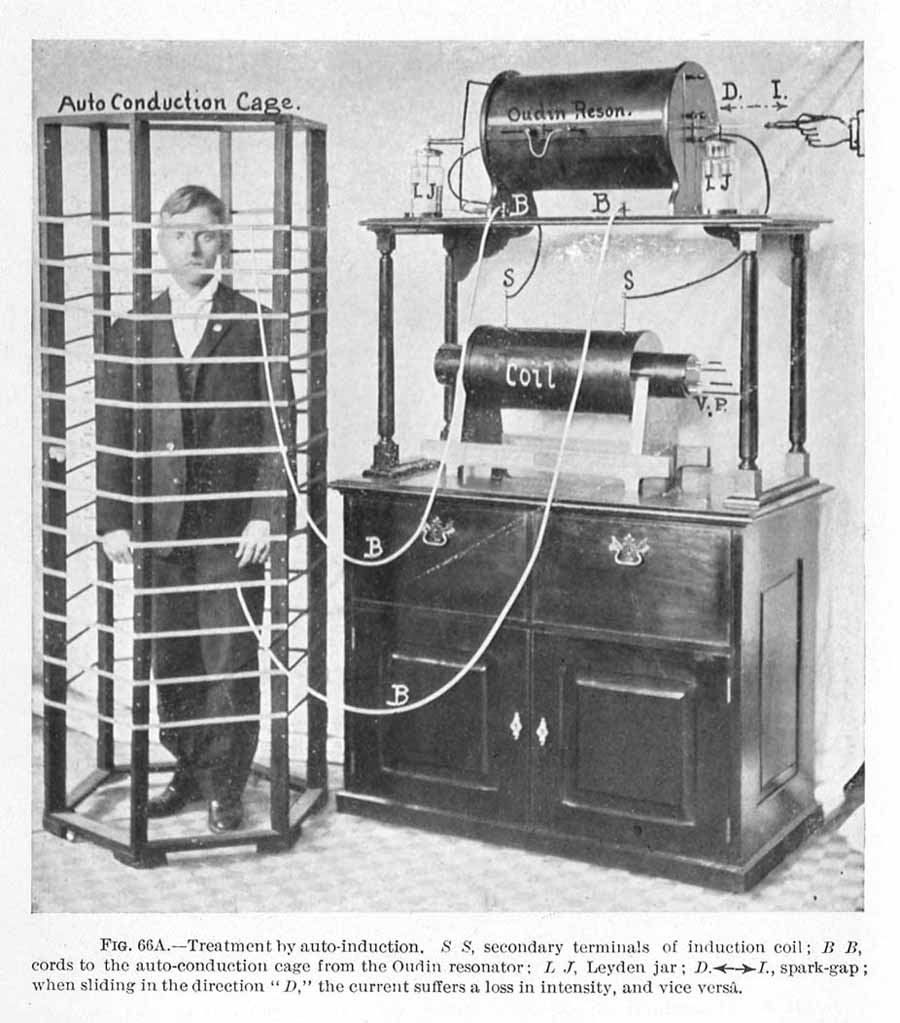

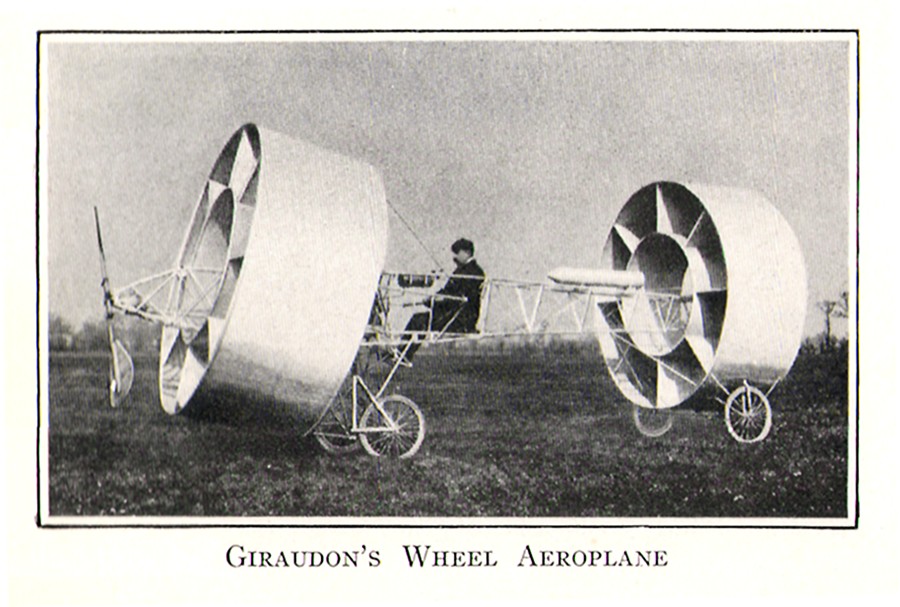

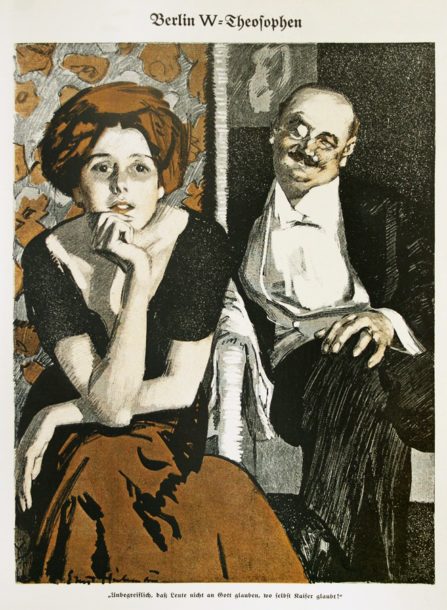

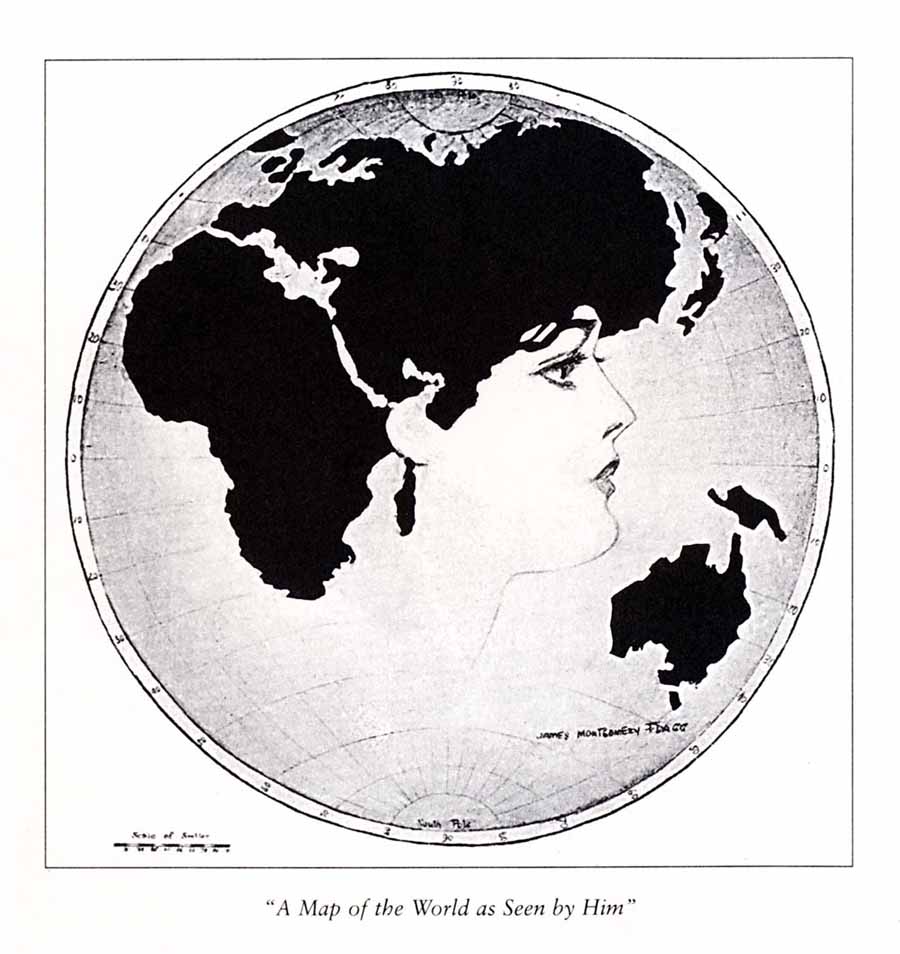

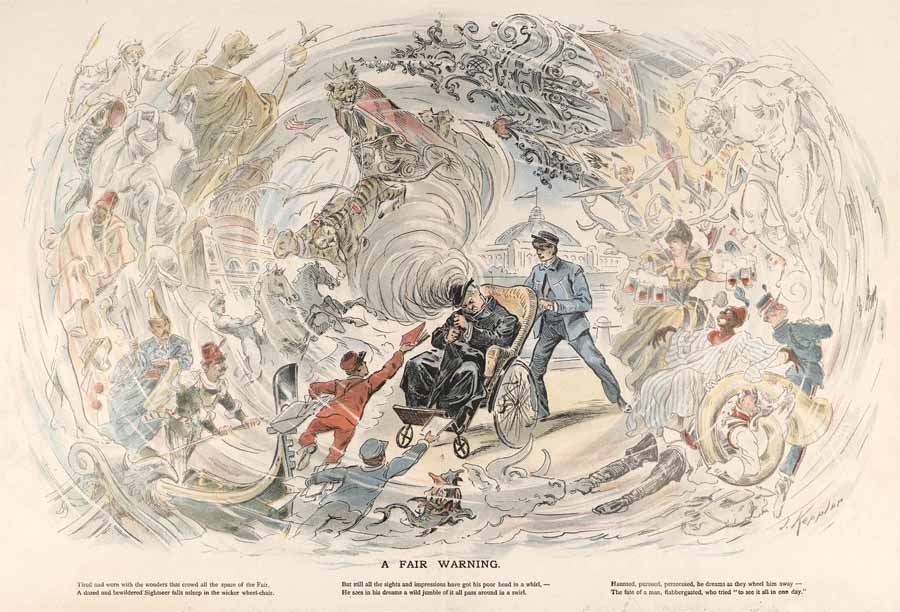

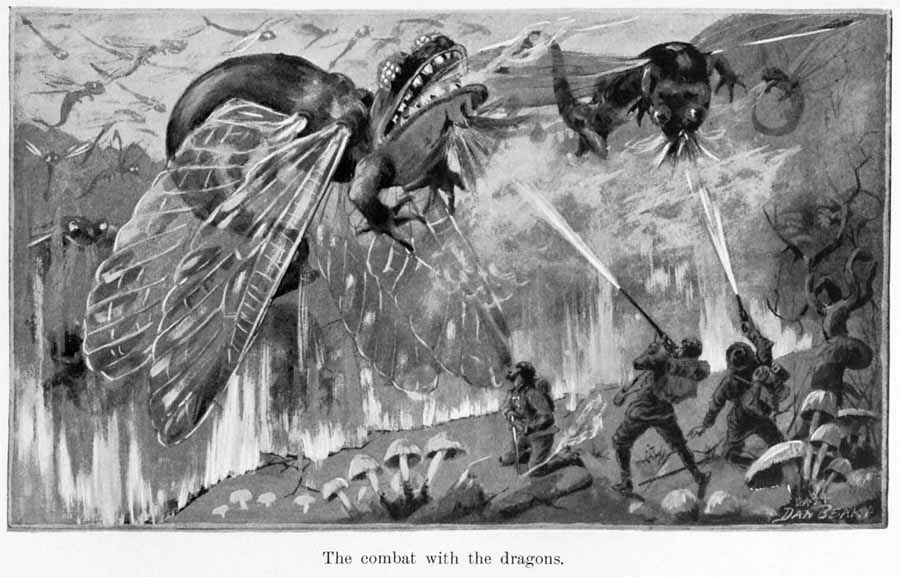

All 2,200 items of the archive have been digitally assembled in an exploratory interface with voice-over narration and sound compositions taken from Harry’s notes. Viewers journey through interactive card clusters of photographs, films, comic illustrations, manuscripts, mechanical drawings, postcards, stereo-cards, and maps spanning the years 1885 to 1925.

The online tale shares the stage with a print book– a novel with historical essays offering an expanded version of the story. Written by Norman M. Klein and Margo Bistis, The Imaginary 20th Century is a multi-media ‘wunder-roman‘, at once a comic picaresque and a treatise on the twentieth century.

Preview the Imaginary 20th Century

Norman M. Klein

The author of the award-winning media novel Bleeding Through: Layers of Los Angeles, 1920-1986 (2003). A cultural critic and historian, much of Klein’s work deals with cities, media and political history. He is also known for his comic scholarly fiction. Among his most influential works are The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory; 7 Minutes: The Life and Death of the American Animated Cartoon; The Vatican to Vegas: A History of Special Effects; Freud in Coney Island and Other Tales; The Imaginary 20th Century and Tales of the Floating Class: Writings, 1982-2017: Essays and Fictions on Globalization and Neo-Feudalism. He teaches at California Institute of the Arts.

Margo Bistis

A cultural historian and curator. Her essays on philosophical modernism, caricature and urban culture have appeared in scholarly journals and anthologies. She is coauthor of The Imaginary 20th Century (ZKM: 2014/16). She teaches at ArtCenter College of Design.

Images from the Archival Narrative

Many facts that lay concealed in the archive are brought to light in the novel. Drag the

images around; double-click to open.

Exhibitions

- Parallel Worlds, Phase Gallery, Los Angeles, 2 November – 14 December 2024.

- Norman M. Klein, The Secret Rise of Skunk Works: 1937 – December 6, 1941, curated by Patrick Winfield Vogel. Office Space Burbank Gallery, Burbank, 7 June – 14 July 2022.

- The Future Can Only Be Told in Reverse: Two Media Novels by Norman M. Klein et al., co-curated by Margo Bistis & Norman Klein. KWI / Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities, Essen, 18 November – 6 December 2019.

- The Imaginary 20th Century, co-curated by Margo Bistis & Norman Klein with Abby Eron. University of Maryland Art Gallery, College Park, 5 September – 30 November 2018.

- The Future Can Only Be Told In Reverse, works by thirteen artists responding to The Imaginary 20th Century, co-curated by Margo Bistis, Norman Klein & Jane Mulfinger. The College of Creative Studies Gallery at the University of California Santa Barbara, 14 February- 9 March 2018.

- The Digital Body: The 3rd International Exhibition on New Media Art, CICA Museum, Gimpo, 12 May- 18 June 2017.

- The Future of the Future, curated by Jaroslav Andel. DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague, 28 July- 24 October 2010.

- Uncharted: User Frames in Media Arts, co-curated by Peter Weibel, Bernhard Serexhe & Ahmet Atif Akin. Santralistanbul, Istanbul, 21 March- 16 August 2009.

- The Future Imaginary, co-curated by Tom Leeser & Meg Linton. Sound installation and works by eleven artists responding to The Imaginary 20th Century. Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Design, Los Angeles, 24 January- 30 March 2009.

- The Imaginary 20th Century, ShowKonstfack, Stockholm, 6-26 October 2008.

- The Imaginary 20th Century, curated by Karen Moss. Orange Lounge, Orange County Museum of Art, Costa Mesa, 17 January- 27 May 2008.

- YOU_ser: The Century of the Consumer, curated by Peter Weibel. ZKM/Center for Art & Media, Karlsruhe, 21 October 2007- 31 December 2008.

Reviews

… The Imaginary 20th Century could be approached as a contemporary version of the classic ‘great American novel’, seen from a more global perspective and including a large number of paratextual and metatextual material. Klein is a great storyteller and the achievement of his work does not only depend on the reader’s amazement (hence the idea of ‘Wunder’, that Renaissance mix of astonishment and admiration we find at the heart of the Wunderkammer aesthetics of this novel) but also on his capacity of striking the right balance between surprise and suspense.

Klein has been a pioneering voice in the progressive disclosure of the mutual shaping and reshaping of storytelling in print and the narrative possibilities of the internet. …The Imaginary 20th Century, a work [co-directed] with cultural historian and curator Margo Bistis, is both a deepening of previous experiments and the result of new reflections on forms and formats of storytelling in the digital age. The novel told in The Imaginary 20th Century resembles more an encyclopedia or if one prepares a creatively treated archive: not just one storyline but four storylines, not just fiction but enhanced fiction, that is fiction completed with substantial visual counterparts as well as faction, often of a very self-reflective type (Klein and Bistis play ball with the reader and viewers, explaining to her the ambition, the context and the procedures of the novel). The images do not ‘illustrate’ the text, they extend it with other means. In a similar vein, the texts do not add narrative or nonnarrative captions to the images, they offer possible interpretations via specific combinations and recombinations of the often astonishing visual material.

Jan Baetens

Image & Narrative

Not a work of hypertext, The Imaginary 20th Century reveals a more humanistic approach to database aesthetics than many other projects…. At its heart, it is a story of seduction. The past is as seductive to the contemporary viewer as the four suitors’ visions of the future are to the heroine.

Kim Beil

Artweek

…Carrie’s archival tale (filled with evasions and contraditions) functions as a psychogeographical diagnostic that for us, operates as a kind of short-circuit — a comic tale potentially snapping many millenials out of their wi-fi induced social media malaise. We must get beyond our fantasmatic, unambiguous visions of the future … And this project moves as fast as you want, or excavates as far as you choose to go. Indeed, without a well-researched sourcebook like this, our premonitions and prognostications will be clouded by too much nostalgia, or false imaginaries.

Maxi Kim

Entropy Magazine

The Imaginary 20th Century not only negotiates the question of where the lines should be drawn between fact and memory, but the book doubles as a puzzle. Its central sentence reads: ‘The future can only be told in reverse’. This aphorism is as paradoxical as it is true. Because after all, it is — among other things– about four visions of the future, but a future that lies in the past; getting reconstructed from the fragments of the archive.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Das Magazin

Selected for Books of the Year, 2016.

Süddeutsche Zeitung